Will You Cry for the Villagers Again Chinese History

| Yue Fei | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Yue Fei | |

| Native name | 岳飛 |

| Born | (1103-03-24)March 24, 1103 Tangyin, Anyang, Henan, China |

| Died | Jan 28, 1142(1142-01-28) (aged 38) Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China |

| Allegiance | Vocal dynasty |

| Years of service | 1122–1142 |

| Battles/wars | Vocal–Jin wars |

| Relations | Yue He (male parent) Lady Yue (mother) |

| Yue Fei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yue's name in Traditional (top) and Simplified (lesser) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 岳飛 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 岳飞 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yue Fei (March 24, 1103 – Jan 28, 1142),[1] courtesy name Pengju ( 鵬舉 ), was a Chinese armed forces general who lived during the Southern Song dynasty, known for leading Southern Song forces in the wars in the twelfth century between Southern Song and the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty in northern China. Because of his warlike-stance, he was put to death by the Southern Song government in 1142 under a concocted charge, after a negotiated peace was achieved with the Jurchens.[ii] Yue Fei is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu ( 無雙譜 , Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Yue Fei's ancestral dwelling house was in Xiaoti, Yonghe Village, Tangyin, Xiangzhou, Henan (in present-day Tangyin County, Anyang, Henan). He was granted the posthumous name Wumu ( 武穆 ) past Emperor Xiaozong in 1169, and after granted the noble title King of È ( 鄂王 ) posthumously past the Emperor Ningzong in 1211. Widely seen every bit a patriot and national folk hero in China, since his decease Yue Fei has evolved into a paragon of loyalty in Chinese culture.

Biographies [edit]

Biography of Yue Fei [edit]

A biography of Yue Fei, the Eguo Jintuo Zubian ( 鄂國金佗稡編 ), was written sixty years after his death by his grandson, the poet and historian Yue Ke ( 岳柯 ) (1183–mail service 1240).[three] [4] [5] In 1346 information technology was incorporated into the History of Song, a 496-chapter record of historical events and biographies of noted Song dynasty individuals, compiled past Yuan dynasty prime number minister Toqto'a and others.[6] Yue Fei's biography is found in the 365th chapter of the book and is numbered biography 124.[7] Some later historians including Deng Guangming (1907–1998) at present doubtfulness the veracity of many of Yue Ke's claims about his grandfather.[eight]

According to the History of Song, Yue Fei was named "Fei", meaning to fly, because at the time he was born, "a large bird like a swan landed on the roof of his house".[9]

Full general Yue Fei [edit]

Relate of Yue, Prince of East of Song [edit]

The Chronicle of Yue, Prince of Eastward of Song (宋岳鄂王年譜; 宋岳鄂王年谱; Sòng Yuè È Wáng Niánpǔ ) was written past Qian Ruwen ( 錢汝雯 ) in 1924.[10]

Nascency and early on life [edit]

Several sources state that Yue was born into a poor tenant farmer'south family in Tangyin County, Anyang prefecture, Henan province.[vii] [11] [12] [13] According to the Shuo Yue Quanzhuan, the immortal Chen Tuan, disguised as a wandering priest, warned Yue Fei's father, Yue He ( 岳和 ), to put his wife and child within a dirt jar if the infant Yue Fei began to cry. A few days subsequently, a young kid squeezed Yue Fei'south paw likewise hard and he began to cry. Before long, it began to rain and the Yellowish River flooded, wiping out the village. Yue Fei's father held onto the clay jar equally it was swept down the river, but eventually drowned. Although the much older Biography of Yue Fei as well mentions the overflowing, it states Yue Huo survived. It reads,

After [the expiry of his teacher Zhou Tong], [Yue Fei] would offer sacrifices at his tomb. His father praised him for his faithfulness and asked him, "When you are employed to cope with the diplomacy of the fourth dimension, volition y'all then not accept to sacrifice yourself for the empire and die for your duty?" ( 侗死,溯望設祭于其冢。父義之,曰:"汝為時用,其徇國死義乎。 )[half-dozen] [7]

Yue Fei's father used his family's plot of land for humanitarian efforts, but subsequently it was destroyed in the flood, the young Yue Fei was forced to aid his father toil in the fields to survive. Yue received nearly of his chief didactics from his father. In 1122 Yue joined the army, but had to return home later that year after the death of his father.[6] In ancient Communist china, a person was required by law to temporarily resign from their job when their parents died so they could observe the customary flow of mourning.[fourteen] For case, Yue would have had to mourn his father'due south death for 3 years, only in all actually only 27 months. During this time, he would wear fibroid mourning robes, caps, and slippers, while abstaining from silken garments.[fifteen] When his mother died in 1136, he retired from a decisive battle against the Jin dynasty for the mourning menstruation, but he was forced to cut the bereavement short considering his generals begged him to come back.[6]

Shuo Yue Quanzhuan gives a very detailed fictional account of Yue's early life. The novel states after being swept from Henan to Hubei, Yue and his mother are saved past the country squire Wang Ming ( 王明 ) and are permitted to stay in Wang's manor every bit domestic helpers. The young Yue Fei later on becomes the adopted son and student of the Wang family's teacher, Zhou Tong, a famous master of military skills. (Zhou Tong is not to be confused with the similarly named "Piffling Tyrant" in H2o Margin.) Zhou teaches Yue and his three sworn brothers – Wang Gui ( 王貴 ), Tang Huai ( 湯懷 ) and Zhang Xian ( 張顯 ) – literary lessons on odd days and military lessons, involving archery and the eighteen weapons of state of war, on even days.[ commendation needed ]

Afterward years of practice, Zhou Tong enters his students into the Tangyin County military examination, in which Yue Fei wins first place by shooting a succession of nine arrows through the bullseye of a target 240 paces abroad. After this display of archery, Yue is asked to marry the daughter of Li Chun ( 李春 ), an former friend of Zhou and the county magistrate who presided over the military examination. However, Zhou soon dies of an affliction and Yue lives by his grave through the winter until the second month of the new year's day when his sworn brothers come up and tear it downward, forcing him to return home and take care of his mother.[ commendation needed ]

Yue eventually marries and later participates in the imperial armed forces test in the Song capital of Kaifeng. In that location, he defeats all competitors and even turns downwardly an offer from Cai Gui ( 蔡桂 ), the Prince of Liang, to be richly rewarded if he forfeits his chance for the armed services caste. This angers the prince and both agree to fight a private duel in which Yue kills the prince and is forced to flee the metropolis for fear of beingness executed. Shortly thereafter, he joins the Song army to fight the invading armies of the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty.[eleven]

The Yue Fei Biography states,

When [Yue] was born, a Peng flew exultation over the business firm, so his father named the child Fei [(飛 – "flight")]. Before [Yue] was even a calendar month old, the Yellow River flooded, and so his female parent got within of the middle of a clay jar and held on to infant Yue. The violent waves pushed the jar down river, where they landed aground ... Despite his family's poverty, [Yue Fei] was studious, and particularly favored the Zuo Zhuan edition of the Spring and Autumn Annals and the strategies of Lord's day Tzu and Wu Qi. ( 飛生時,有大禽若鵠,飛鳴室上,因以為名。未彌月,河決內黃,水暴至,母姚抱飛坐瓮中,衝濤及岸得免,人異之。-- 家貧力學,尤好【左氏春秋】、孫吳兵法。 )[7]

Co-ordinate to a book by martial arts master Liang Shouyu, "[A] Dapeng is a great bird that lived in ancient China. Fable has it, that Dapeng Jinchi Mingwang was the guardian that stayed in a higher place the caput of Gautama Buddha. Dapeng could get rid of all evil in any area. Even the Monkey King was no lucifer for it. During the Song dynasty the government was decadent and foreigners were constantly invading China. Sakyamuni sent Dapeng down to globe to protect China. Dapeng descended to Earth and was born as Yue Fei."[16]

Martial training [edit]

Illustration of Zhou Tong, Yue Fei's teacher

The Biography of Yue Fei states, "Yue Fei possessed supernatural ability and before his adulthood, he was able to depict a bow of 300 catties (400 pounds (180 kg)) and a crossbow of eight stone (960 catties, 1,280 pounds (580 kg)). Yue Fei learned archery from Zhou Tong. He learned everything and could shoot with his left and right easily."[7] [17] [10] [16] [xviii] Shuo Yue Quanzhuan states Zhou teaches Yue and his sworn brothers archery and all of the eighteen weapons of war. This novel also says Yue was Zhou's tertiary student after Lin Chong and Lu Junyi of the 108 outlaws in Water Margin. The Eastward Wang Shi records, "When Yue Fei reached adulthood, his maternal gramps, Yao Daweng ( 姚大翁 ), hired a spear expert, Chen Guang, to teach Yue Fei spear fighting."[nineteen] [20]

Both the Biography of Yue Fei and E Wang Shi mention Yue learning from Zhou and Chen at or before his machismo. The Chinese character representing "machismo" in these sources is ji guan (Chinese: 及冠; pinyin: jí guàn ; lit. 'conferring headdress'), an ancient Chinese term that ways "20 years one-time" where a young human was able to wearable a formal headdress as a social status of adulthood.[21] [22] Then he gained all of his martial arts knowledge by the time he joined the ground forces at the age of 19.[7] [xviii]

These chronicles exercise not mention Yue'southward masters education him martial arts fashion; but archery, spearplay and military machine tactics. However non-historical or scholarly sources state, in addition to those already mentioned, Zhou Tong taught Yue other skills such as mitt-to-paw combat and horseback riding. Still once again, these exercise non mention any specific martial arts style. One legend says Zhou took young Yue to an unspecified identify to meet a Buddhist hermit who taught him the Emei Dapeng qigong ( 峨嵋大鵬氣功 ) fashion. This is supposedly the source of his legendary force and martial arts abilities.[12] [sixteen] According to thirteenth generation lineage Tai He ("Great Harmony") Wudangquan master Fan Keping ( 范克平 ), Zhou Tong was a main of various "hard qigong" exercises.[23] [24]

Yue Fei's female parent writes jin zhong bao guo on his back, as depicted in a "Suzhou style" beam decoration at the Summer Palace, Beijing.

Yue Fei'southward tattoo [edit]

According to historical records and legend, Yue had the iv Chinese characters jin zhong bao guo (traditional Chinese: 盡忠報國; simplified Chinese: 尽忠报国; pinyin: jìn zhōng bào guó ; lit. 'serve the land with the utmost loyalty') tattooed across his back. The Biography of Yue Fei says later Qin Hui sent agents to abort Yue and his son, he was taken before the court and charged with treason, only

飛裂裳以背示鑄,有盡忠報國四大字,深入膚理。既而閱實無左驗,鑄明其無辜。

Yue ripped his jacket to reveal the four tattooed characters of "serve the country with the utmost loyalty" on his back. This proved that he was clearly innocent of the charges.[7]

Later fictionalizations of Yue's biography would build upon the tattoo. For instance, ane of his primeval Ming era novels titled The Story of King Yue Who Restored the Song dynasty ( 大宋中興岳王傳 ) states that afterwards the Jurchen armies invaded People's republic of china, young heroes in Yue's hamlet suggest that they bring together the bandits in the mountains. Notwithstanding, Yue objects and has one of them tattoo the aforementioned characters on his dorsum. Whenever others want to join the bandits, he flashes them the tattoo to change their minds.[25]

Portion of the stele mentioning the tattoo

The common legend of Yue receiving the tattoo from his mother starting time appeared in Shuo Yue Quanzhuan. In chapter 21 titled "Past a pretext Wang Zuo swore brotherhood, past tattoos Lady Yue instructed her son", Yue denounces the pirate chief Yang Yao ( 楊幺 ) and passes on a take a chance to become a general in his army. Yue Fei's female parent then tells her son, "I, your mother, saw that you did not accept recruitment of the rebellious traitor, and that you willingly endure poverty and are not tempted by wealth and status ... Merely I fear that subsequently my death, there may be some unworthy fauna who will entice you ... For these reason ... I want to tattoo on your dorsum the four characters 'Utmost', 'Loyalty', 'Serve' and 'Nation' ... The Lady picked upward the castor and wrote out on his spine the four characters for 'serving the nation with the utmost loyalty' ... [So] she chip her teeth, and started pricking. Having finished, she painted the characters with ink mixed with vinegar so that the colour would never fade."[eleven]

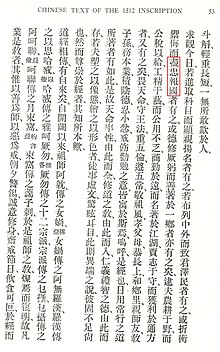

The Kaifeng Jews, one of many pockets of Chinese Jews living in ancient China, refer to this tattoo in two of their three stele monuments created in 1489, 1512, and 1663. The first mention appeared in a section of the 1489 stele referring to the Jews' "Dizzying loyalty to the country and Prince".[26] The second appeared in a department of the 1512 stele nigh how Jewish soldiers and officers in the Chinese armies were "boundlessly loyal to the state".[27]

Adult life [edit]

Portrait [edit]

Southern Vocal era artist Liu Songnian ( 劉松年 ) (1174–1224), who was best known for his realistic works, painted a flick, "Four Generals of Zhongxing" ( 中興四將 ).[28] The group portrait shows eight people – iv generals and four attendants. Starting from the left: attendant, Yue Fei, bellboy, Zhang Jun ( 張浚 ), Han Shizhong ( 韓世忠 ), attendant, Liu Guangshi ( 劉光世 ), and attendant.[29]

According to history professor He Zongli of Zhejiang University, the painting shows Yue was more of a scholarly-looking full general with a shorter stature and chubbier build than the statue of him currently displayed in his tomb in Hangzhou, which portrays him as being tall and skinny. Shen Lixin, an official with the Yue Fei Temple Administration, holds the portrait of Yue Fei from the "Iv Generals of Zhongxing" to exist the about authentic likeness of the general in being.[xxx]

Character [edit]

Calligraphy written by Yue Fei

In his From Myth to Myth: The Example of Yüeh Fei's Biography, noted Sinologist Hellmut Wilhelm[31] concluded that Yue Fei purposely patterned his life after famous Chinese heroes from dynasties past and that this ultimately led to his martyrdom.[6] Apart from studying literature under his father Yue He ( 岳和 ), Yue Fei loved to read armed services classics. He favored the Zuo Zhuan commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals and the strategies of Sun Tzu and Wu Qi. Although his literacy afforded him the risk to get a scholar, which was a position held in much higher regard than the mutual soldiery during the Song dynasty, Yue chose the military path because there had never been any tradition of civil service in his family unit. Therefore he had no reason to study Confucian classics in society to surpass the accomplishments of his ancestors or to heighten his family's social status to the next level. His fourth generation ancestor, Yue Huan ( 岳渙 ), had served as a lingshi ( 令使 ) (substantially a low-level functionary),[32] but he was never a full-fledged member of the civil service rank.[33] A second theory is that he joined the armed forces in the hopes of emulating his favorite heroes.[6]

Scholars were ever welcome in Yue Fei's camp. He immune them to come up and tell stories and deeds of by heroes to bolster the resolve of his men. This way he was able to teach them almost the warriors that he had constructed his own life later. He also hoped that one of these scholars would record his own deeds and then he would become a peer amongst his idols. He is recorded in proverb that he wished to be considered the equal of Guan Yu and other such famous men from the Three Kingdoms period. Yue succeeded in this endeavor since later on "official mythology" placed him on the same level as Guan Yu.[6]

Yue was careful to conduct himself equally the platonic Confucian gentleman at all times for fear that whatsoever misconduct would be recorded and criticized by people of later dynasties. However he had his faults. He had a trouble with booze during the early part of his military career. Yue drank in great excess because he believed it fitted the paradigm of heroes of old. However one time he most killed a colleague in a drunken rage, the emperor made him promise not to beverage any more until the Jurchen invaders had been driven away.[vi]

Family [edit]

Yue Yun ( 岳雲 ), Yue Fei's eldest son

According to Shuo Yue Quanzhuan, Yue had v sons and i girl. The History of Song records that Yue Yun ( 岳雲 ; 1119–1142) was adopted past Yue Fei at the age of 12[34] whilst others claim he was his biological son;[20] Yue Lei ( 岳雷 ), the second, succeeded to his begetter'south mail; Yue Ting ( 岳霆 ) was the tertiary; Yue Lin ( 岳霖 ) was the fourth; and Yue Zhen ( 岳震 ), the fifth, was still immature at the time of his father's decease. Yue Yinping was Yue Fei's daughter. The novel states she committed suicide after her father's decease and became a fairy in sky. All the same, history books practice non mention her name and therefore she should be considered a fictional character.[xx] Yue Fei married the daughter of Magistrate Li in 1119 when he was 16 years old.[11] However, the account of his marriage is fictional.[twenty]

The Biography of Yue Fei states that Yue left his ailing mother with his first wife while he went to fight the Jin armies. Notwithstanding she "left him (and his mother) and remarried".[vi] He afterwards took a 2d wife and fifty-fifty discussed "diplomacy" pertaining to his military career with her. He truly loved her, but his affection for her was 2nd to his desire to rid China of the Jurchen invaders. Her faithfulness to him and his mother was strengthened by the fear that any infidelity or lacking in her care of Lady Yue would result in reprisal.[6]

Yue forbade his sons from having concubines, although he about took one himself. Even though she was presented by a friend, he did not take her because she laughed when he asked her if she could "share the hardships of camp life" with him.[half dozen] He knew she was liberal and would have sex with the other soldiers.[six]

Though not mentioned in the memoir written by Yue Fei's grandson, some scholarly sources claim Yue had a younger brother named Yue Fan ( 岳翻 ). He subsequently served in the army under his blood brother and died in battle in 1132.[20]

Military record [edit]

Map showing the Song-Jurchen Jin wars with Yue Fei'south northern expedition routes

Battles of Yancheng, Yingchang and Zhuxianzhen, which occurred during the last northern expedition led by Yue Fei

The son of an impoverished farmer from northern China, Yue Fei joined the Song military in 1122.[35] Yue briefly left the army when his begetter died in 1123, but returned in 1126.[36] Later on reenlisting, he fought to suppress rebellions by local Chinese warlords responsible for looting in northern China. Local uprisings had diverted needed resources abroad from the Vocal'south war against the Jin.[37] Yue participated in defending Kaifeng during the second siege of the city past the Jin in 1127. Afterward Kaifeng vicious, he joined an army in Jiankang tasked with defending the Yangtze. This army prevented the Jurchens from advancing to the river in 1129.[38] His rising reputation every bit a war machine leader attracted the attention of the Vocal courtroom. In 1133, he was made the general of the largest ground forces almost the Primal Yangtze.[39] Betwixt 1134 and 1135, he led a counteroffensive confronting Qi, a puppet state supported by the Jin, and secured territories that had been conquered by the Jurchens.[40] He continued to advance in rank, and to increase the size of his ground forces as he repeatedly led successful offensives into northern China. Several other generals were also successful against the Jin dynasty, and their combined efforts secured the survival of the Song dynasty. Yue, like nigh of them, was committed to recapturing northern China.[ citation needed ]

Stone Lake: The Poetry of Fan Chengda 1126–1193 states, "...Yue Fei ([1103]-1141)...repelled the enemy assaults in 1133 and 1134, until in 1135 the now confident Song army was in a position to recover all of n Communist china from the Jin dynasty ... [In 1140,] Yue Fei initiated a general counterattack against the Jin armies, defeating one enemy later on another until he fix up military camp inside range of the Northern Vocal dynasty'southward old capital urban center, Kaifeng, in grooming for the final assault confronting the enemy. Even so in the same year Qin [Hui] ordered Yue Fei to abandon his campaign, and in 1141 Yue Fei was summoned back to the Southern Vocal capital. Information technology is believed that the emperor then ordered Yue Fei to be hanged."[41]

Battle of Zhuxianzhen near Kaifeng in Henan where Yue Fei defeated the Jin army in 1140. Painting on the Long Corridor of the Summer Palace in Beijing.

Six methods for deploying an regular army [edit]

Yue Ke ( 岳珂 ) states his granddad had vi special methods for deploying an ground forces effectively:

- Careful option

- He relied more on modest numbers of well-trained soldiers than he did large masses of the poorly trained multifariousness. In this style, one superior soldier counted for every bit much every bit one hundred inferior soldiers. One case used to illustrate this was when the armies of Han Ching and Wu Xu were transferred into Yue'due south camp. Most of them had never seen boxing and were by and large also old or unhealthy for sustaining prolonged troop movement and engagement of the enemy. Once Yue had filtered out the weak soldiers and sent them home, he was only left with a meager 1000 able-bodied soldiers. However, after some months of intense preparation, they were ready to perform virtually as well as the soldiers who had served under Yue for years.[6]

- Careful training

- When his troops were not on military campaigns to win back lost Chinese territory in the north, Yue put his men through intense preparation. Apart from troop move and weapons drills, this training also involved them leaping over walls and crawling through moats in full battle garb. The intensity of the preparation was such that the men would not even effort to visit their families if they passed past their homes while on movement and even trained on their days off.[6]

- Justice in rewards and punishments

- He rewarded his men for their merits and punished them for their boasting or lack of grooming. Yue once gave a foot soldier his own personal belt, silver dinner ware, and a promotion for his meritorious deeds in boxing. While on the reverse, he once ordered his son Yue Yun to be decapitated for falling off his equus caballus subsequently declining to leap a moat. His son was only saved after Yue's officers begged his mercy. There were a number of soldiers that were either dismissed or executed because they boasted of their skills or failed to follow orders.[half-dozen]

- Clear orders

- He always delivered his orders in a unproblematic manner that was easy for all of his soldiers to sympathize. Whoever failed to follow them were severely punished.[6]

- Strict discipline

- While marching most the countryside, he never permit his troops destroy fields or to pillage towns or villages. He made them pay a fair price for goods and fabricated sure crops remained intact. A soldier once stole a hemp rope from a peasant so he could tie a bale of hay with it. When Yue discovered this, he questioned the soldier and had him executed.[vi]

- Close fellowship with his men

- He treated all of his men similar equals. He ate the same food as they did and slept out in the open up as they did. Even when a temporary shelter was erected for him, he made sure several soldiers could find room to slumber within earlier he found a spot of his own. When there was not plenty wine to get around, he would dilute it with h2o so every soldier would receive a portion.[6]

Death [edit]

In 1126, several years before Yue became a general, the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty invaded northern Mainland china, forcing the Song dynasty out of its uppercase Kaifeng and capturing Emperor Qinzong of Song, who was sent into captivity in Huining Prefecture. This marked the end of the Northern Song dynasty, and the beginning of the Southern Song dynasty under Emperor Gaozong.

Yue fought a long campaign confronting the invading Jurchen in an endeavour to retake northern Mainland china. Only every bit he was threatening to attack and retake Kaifeng, officials advised Emperor Gaozong to recall Yue to the upper-case letter and sue for peace with the Jurchen. Fearing that a defeat at Kaifeng might cause the Jurchen to release Emperor Qinzong, threatening his claim to the throne, Emperor Gaozong followed their advice, sending 12 orders in the class of 12 aureate plaques to Yue Fei, recalling him dorsum to the uppercase. Knowing that a success at Kaifeng could lead to internal strife, Yue submitted to the emperor's orders and returned to the capital, where he was imprisoned and where Qin Hui would eventually arrange for him to exist executed on false charges.[eleven]

There are conflicting views on how Yue died. According to The History of China: (The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations) and other sources, Yue died in prison.[12] [42] The Chronicle of Yue, Prince of Eastward of Vocal says he was killed in prison.[7] Shuo Yue Quanzhuan states he was strangled to death. It reads, "...[Yue Fei] strode in long steps to the Pavilion of Winds and Waves ... The warders on both sides picked up the ropes and strangled the iii men [Yue Fei, Yue Yun, and Zhang Xian ( 張憲 ), Yue's subordinate] without farther ado ... At the fourth dimension Lord Yue was 39 years of historic period and the young lord Yue Yun 23. When the three men returned to Heaven, all of a sudden a vehement current of air rose up wildly and all the fires and lights were extinguished. Black mists filled the sky and sand and pebbles were blown nearly."[11]

The Secrets of Eagle Hook Kung Fu: Ying Jow Pai comments, "Finally, [Yue Fei] received the 'Twelfth Golden Edict' [from the emperor calling him back to the capital], which if ignored meant adjournment. Patriotism demanded that he obey. On his way back to the capital he stopped to rest at a pavilion. Qin Hui anticipated Yue Fei's route and sent some men to lie in wait. When Yue Fei arrived, Qin'south men ambushed and murdered him. Just 39 years former, Yue Fei like many good men in history, had a swift, brilliant career, so died brutally while still immature."[43]

Co-ordinate to A Chinese Biographical Dictionary, "[Father and son] had non been two months in confinement when Qin Hui resolved to rid himself of his enemy. He wrote out with his own hand an order for the execution of Yue Fei, which was forthwith carried into issue; whereupon he firsthand reported that Yue Fei had died in prison",[13] which meant that Qin Hui had Yue and his son executed but reported they both died in captivity.

Other sources say he was poisoned to death.[44] [45] Still, a slap-up number simply say he was executed, murdered, or "treacherously assassinated".[46] [47] [48]

After Yue's execution, a prison officer, Wei Shun ( 隗順 ), who admired Yue'southward character, stole his body and secretly buried information technology at the Nine Vocal Cong Temple ( 九曲叢祠 ) located exterior the Song capital.[49]

Qin Hui'southward posthumous penalisation [edit]

Shuo Yue Quanzhuan states after having Yue Fei, Yue Yun, Zhang Xian arrested nether fake charges, Qin Hui and his wife, Lady Wang ( 王氏 ), were sitting by the "eastern window", warming themselves past the burn, when he received a letter from the people calling for the release of Yue Fei. Qin was worried because afterward nearly two months of torture, he could not get Yue to acknowledge to treason and would eventually take to let him go. Yet, after a servant daughter brought fresh oranges into the room, Lady Wang devised a programme to execute Yue. She told Qin to slip an execution discover inside the pare of an orange and send it to the guess presiding over Yue's case. This way, Yue and his companions would be put to expiry before the emperor or Qin himself would have to rescind an open club of execution.[11] This conspiracy became known as the "East Window Plot".[50] A novel near this incident, titled Dong Chuang Ji ( 東窗記 ; "Tale of the Eastern Window"), was written during the Ming dynasty by an anonymous writer.[51]

When confronted by Han Shizhong on what crime Yue had committed, Qin Hui replied, "Though information technology isn't sure whether there is something that he did to beguile the dynasty, maybe at that place is." The phrase "perhaps there is", "no reason needed", "groundless", or "baseless" (Chinese: 莫須有; pinyin: mò xū yǒu ) has entered Chinese language as a saying to refer to fabricated charges,[52] which also means 'trumped-up accuse', 'setup', 'frameup', or 'concocted charge', in English language. At that place is a poem hanging on the gate surrounding the statues that reads, "The green hill is fortunate to be the burial ground of a loyal general, the white iron was innocent to be cast into the statues of traitors."[53]

Decades later on, his grandson, Yue Ke ( 岳珂 ), had retrieved documentary bear witness of his grandfather's achievements, and published an adulatory biography of him. In 1162 Emperor Xiaozong of Vocal posthumously pardoned and rehabilitated his honours. For their part in Yue'southward death, iron statues of Qin Hui, Lady Wang, and 2 of Qin'due south subordinates, Moqi Xie ( 万俟卨 ) and Zhang Jun ( 張俊 ), were made to kneel before Yue Fei's tomb (located by the West Lake, Hangzhou). For centuries, these statues take been cursed, spat and urinated upon past people. The original castings in statuary were damaged, but afterward were replaced by images cast in atomic number 26, but these were similarly damaged. All the same now, in mod times, these statues are protected every bit historical relics.[54] Emperor Xiaozong'due south court gave proper burial to his remains after Wei Shun's family revealed its location;[49] Wei Shun was and then posthumously honored at Yue Fei's hometown at Tangyin Canton, and a statue of him was made standing at its Yue Fei Temple. A [tomb] was put upwardly in his memory, and he was designated Wumu ( 武穆 ; "Martial and Stern"). In 1179 he was canonized as Zhongwu ( 忠武 ; "Loyal and Martial").[13] [55]

According to the novel Xi Yous Bu, a satire of Journey to the West, written in 1641 by the scholar Dong Ruoyu (also known equally Dong Yue, 1620–1686), the Monkey King enthusiastically serves in hell every bit the trial prosecutor of Qin Hui, while Yue Fei becomes the Monkey Rex's third master (by teaching the latter Confucian methods). At one point, the Monkey King asks the spirit of Yue Fei if he would like to potable Qin's blood, but he politely declined.[51]

-

Map of the West Lake with the location of the Temple of Yue Fei

Talents [edit]

Martial arts [edit]

The 2 styles virtually associated with Yue are Eagle Claw and Xingyi boxing. One book states Yue created Eagle Claw for his enlisted soldiers and Xingyi for his officers.[56] Legend has it that Yue studied in the Shaolin Monastery with a monk named Zhou Tong and learned the "elephant" manner of battle, a set up of mitt techniques with great emphasis on qinna (joint-locking).[43] [57] [58] Other tales say he learned this style elsewhere exterior the temple under the same master.[12] Yue somewhen expanded elephant style to create the Yibai Lingba Qinna ( 一百零八擒拿 ; "108 Locking Mitt Techniques") of the Ying Sao (Eagle Easily) or Ying Kuen (Hawkeye Fist).[43] Later becoming a full general in the royal regular army, Yue taught this style to his men and they were very successful in battle confronting the armies of the Jin dynasty.[12] Following his wrongful execution and the disbandment of his armies, Yue's men supposedly traveled all over China spreading the style, which somewhen ended right back in Shaolin where it began. Later, a monk named Li Quan ( 麗泉 ) combined this style with Fanziquan, another manner attributed to Yue, to create the modern day form of Northern Ying Jow Pai boxing.[43] [59]

According to legend, Yue combined his knowledge of internal martial arts and spearplay learned from Zhou Tong (in Shaolin) to create the linear fist attacks of Xingyi battle.[12] [sixty] Ane volume claims he studied and synthesized Buddhism's Tendon Changing and Marrow Washing qigong systems to create Xingyi.[61] On the reverse, proponents of Wudangquan believe it is possible that Yue learned the style in the Wudang Mountains that border his home province of Henan. The reasons they cite for this conclusion are that he supposedly lived around the same fourth dimension and place as Zhang Sanfeng, the founder of t'ai chi; Xingyi'due south 5 fist attacks, which are based on the Five Chinese Elements theory, are like to tai-chi's "Yin-yang theory"; and both theories are Taoist-based and not Buddhist.[62] The book Henan Orthodox Xingyi Quan, written by Pei Xirong ( 裴锡荣 ) and Li Ying'ang ( 李英昂 ), states Xingyi master Dai Longbang

... wrote the 'Preface to Six Harmonies Boxing' in the 15th reign year of the Qianlong Emperor [1750]. Within it says, '... when [Yue Fei] was a child, he received special instructions from Zhou Tong. He became extremely skilled in the spear method. He used the spear to create methods for the fist. He established a method called Yi Quan [意拳]. Mysterious and unfathomable, followers of old did not have these skills. Throughout the Jin, Yuan and Ming dynasties few had his fine art. Only Ji Gong had it. ( 於乾隆十五年為"六合拳"作序云:"岳飛當童子時,受業於周侗師,精通槍法,以槍为拳,立法以教將佐,名曰意拳,神妙莫測,盖从古未有之技也。 )[63] [64]

Within the grounds of Yue Fei'due south tomb and shrine in Hangzhou; the inscriptions at the far end read "Serve the country with the utmost loyalty".

The Ji Gong mentioned above, better known as Ji Jike ( 姬際可 ) or Ji Longfeng ( 姬隆丰 ), is said to take trained in Shaolin Monastery for ten years as a swain and was matchless with the spear.[threescore] Every bit the story goes, he afterward traveled to Xongju Cave on Mountain Zhongnan to receive a battle transmission written by Yue Fei, from which he learned Xingyi. However, some believe Ji actually created the style himself and attributed information technology to Yue Fei considering he was fighting the Manchus, descendants of the Jurchens who Yue had struggled against.[65] Ji supposedly created it after watching a battle between an hawkeye and a bear during the Ming dynasty.[66] Other sources say he created it while training in Shaolin. He was reading a book and looked up to see ii roosters fighting, which inspired him to imitate the fighting styles of animals.[60] [67] [68] Both versions of the story (hawkeye / carry and roosters) state he continued to written report the actions of animals and eventually increased the cadre of animal forms.[60]

Several other martial arts take been attributed to Yue Fei, including Yuejiaquan (Yue Family Boxing), Fanziquan (Tumbling Boxing), and Chuōjiǎo quan (Feet-Poking Boxing), amongst others.[69] [lxx] [71] The "Fanzi Boxing Ballad" says: "Wumu has passed down the Fanziquan which has mystery in its straightforward movements." Wumu ( 武穆 ) was a posthumous name given to Yue after his death.[xiii] Ane Chuojiao legend states Zhou Tong learned the style from its creator, a wandering Taoist named Deng Liang ( 鄧良 ), and later passed it onto Yue Fei, who is considered to be the progenitor of the manner.[69] [72]

Also martial arts, Yue is also said to have studied traditional Chinese medicine. He understood the essence of Hua Tuo's Wu Qin 11 ( 五禽戲 ; "V Fauna Frolics") and created his ain form of "medical qigong" known equally the Ba Duan Jin ( 八段錦 ; "Viii Pieces of Brocade"). Information technology is considered a course of Waidan ( 外丹 ; "External Elixir") medical qigong.[73] He taught this qigong to his soldiers to help go along their bodies potent and well-prepared for battle.[74] [75] One legend states that Zhou Tong took young Yue to meet a Buddhist hermit who taught him Emei Dapeng Qigong ( 峨嵋大鵬氣功 ). His training in Dapeng Qigong was the source of his neat force and martial arts abilities. Modernistic practitioners of this style say it was passed down by Yue.[xvi]

Connection to Praying Mantis boxing [edit]

According to Shuo Yue Quanzhuan, Lin Chong and Lu Junyi of the 108 outlaws in Water Margin were former students of Yue'due south teacher Zhou Tong.[76] One legend states Zhou learned Chuōjiǎo boxing from its originator Deng Liang ( 鄧良 ) and so passed it onto Yue Fei, who is sometimes considered the progenitor of the mode.[69] Chuojiao is also known as the "H2o Margin Outlaw style" and Yuanyang Tui ( 鴛鴦腿 ; "Mandarin Duck Leg").[77] In chapter 29 of H2o Margin, titled "Wu Song beats Jiang the Door God in a drunken daze", information technology mentions Wu Vocal, another of Zhou'southward fictional students, using the "Jade Circle-Steps with Duck and Drake anxiety".[78] A famous folklore Praying Mantis manuscript, which describes the fictional gathering of eighteen martial arts masters in Shaolin, lists Lin Chong (#thirteen) as a master of "Mandarin ducks kicking technique".[69] This creates a folklore connection between Yue and Mantis boxing.

Lineage Mantis chief Yuen Man Kai openly claims Zhou Tong taught Lin Chong and Lu Junyi the "same schoolhouse" of martial arts that was afterwards combined with the same seventeen other schools to create Mantis fist.[79] However, he believes Mantis fist was created during the Ming dynasty, and was therefore influenced by these eighteen schools from the Song dynasty. He as well says Lu Junyi taught Yan Qing the same martial arts every bit he learned from Zhou Tong.[fourscore] Yuen further comments that Zhou Tong later on taught Yue Fei the same martial art and that Yue was the originator of the mantis motility "Blackness Tiger Stealing [sic] Heart".[80]

Poetry [edit]

At the age of 30, Yue supposedly wrote his almost celebrated verse form, "Human Jiang Hong" ("Entirely Red River") with a subtitle of "Xie Huai" ("Writing almost What I Thought"). This poem reflects the raw hatred he felt towards the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty, likewise as the sorrow he felt when his efforts to compensate northern lands lost to Jin were halted by Southern Song officials of the "Peace Faction". Still, several modern historians, including the late Princeton Academy Prof. James T. C. Liu, believe certain phrasing in the poem dates its cosmos to the early on 16th century, significant Yue did non write it.[81]

Yue Fei is also the writer of at least ii other poems, "Xiao Chong Shan" ("Minor Hills") and another "Human being Jiang Hong" with a subtitle of "Deng Huang He Lou Y'all Gan" ("My Feelings When I Was Climbing the Xanthous Crane Pavilion").

Descendants [edit]

Amongst Yue Fei's descendants was Yue Shenglong ( 岳昇龍 ) and his son the Qing dynasty official Yue Zhongqi,[82] who served equally Minister of Defense and Governor-General of Shaanxi and Gansu provinces during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor. Yue Zhongqi conquered Tibet for the Qing during the Dzungar–Qing War and attacked the Dzungars at Ürümqi in Xinjiang.[83] [84] The Oirats were battled against by Yue Zhongqi.[85] Yue Zhongqi lived at the Ji Xiaolan Residence.

Another notable descendant of Yue Fei was Yue Yiqin, a flight ace of the Republic of People's republic of china during the 2nd Sino-Japanese State of war.[86]

In 2011, two Yue descendants, Yue Jun and Yue Haijun, with six members of their clan, protested Jiangning Purple Silk Manufacturing Museum's Qin Hui statue, which indicates that even afterward centuries, the Yue family unit still hates Qin Hui and his conspirators for their ancestors' plights. Information technology is also reportedly that the Yue family members were not allowed to marry anyone whose surname was as well Qin until 1949, and hardly anyone break this dominion prior to it being nulled.[87] By 2017, it is reported that Yue Fei's descendants are 1.81 million people in Mainland china, and only Yue Fei's descendants in Anhui Province have grown to more than one.003 million.[88]

Folk hero [edit]

From the Four Generals of Zhongxing painted by Liu Songnian in 1214, 72 years after the expiry of Yue Fei.

Yue Fei'south stature in Chinese history rose to that of a national folk hero afterward his execution.[89] Qin Hui, and in some cases Emperor Gaozong, were blamed by later historians for their supposed role in Yue Fei'south execution and conciliatory stance with the Jin dynasty.[90] The allegations that Qin Hui conspired with the Jin to execute Yue Fei are pop in Chinese literature, but have never been proven.[91] The existent Yue Fei differed from the later myths that grew from his exploits.[92] The portrayal of Yue equally a scholar-full general is only partially true. He was a skilled general, and may have been partially literate in Classical Chinese, merely he was not an erudite Confucian scholar.[36] Reverse to traditional legends, Yue was not the sole Chinese full general engaged in the offensive against the Jurchens. He was ane of many generals that fought against the Jin in northern China, and unlike Yue Fei, some of his peers were genuine members of the scholarly elite.[39] Many of the exaggerations of Yue Fei's life can exist traced to a biography written by his grandson, Yue Ke. Yue Fei's condition as a folk hero strengthened in the Yuan dynasty and had a big bear upon on Chinese civilisation.[93] Temples and shrines devoted to Yue Fei were synthetic in the Ming dynasty. A Chinese Globe War 2 anthem alludes to lyrics said to have been written by Yue Fei.[94]

He also sometimes appears as a door god in partnership with the deity Wen Taibao.[ commendation needed ]

At certain points in fourth dimension, Yue Fei ceased to be a national hero, such as in 2002, when the official guidelines for history teachers said that he could no longer behave the title. This was considering Yue Fei had defended Prc from the Jurchen people, who are presently considered to be a part of the Chinese nation. Therefore, concern for the "unity of nationalities" in China prevailed, equally Yue Fei was seen as representing only one subgroup within China, and non the "entire Chinese nation as presently divers".[95] However, both the Chinese Ministry building of Didactics and the Minister of Defence deny such claims and still clearly address Yue Fei as a national hero of China.[96] [97] The Chinese Communist Party likewise continues to treat Yue Fei as a national hero of China.[98]

Modernistic references [edit]

The ROCS Yueh Fei (FFG-1106), a Cheng Kung-grade guided-missile frigate of the Republic of Red china Navy, is named after Yue.

The writer Guy Gavriel Kay cites Yue Fei every bit having inspired the graphic symbol Ren Daiyan in his novel River of Stars (ISBN 978-0-670-06840-1), which is set in a fantasy world based on Song Dynasty Prc.

Yue Fei is one of the 32 historical figures who announced as special characters in the video game Romance of the Three Kingdoms Eleven by Koei.[ citation needed ]

See also [edit]

- Cultural depictions of Yue Fei

- Yue Fei Temple

- Tomb of Yue Fei

- Han Shizhong

- Zhang Jun

- Wen Tianxiang

- Lu Xiufu

- Zhang Shijie

- History of the Song dynasty

- Jin–Song Wars

- Timeline of the Jin–Vocal wars

- Yuan Chonghuan

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Mair, Victor H.; Chen, Sanping; Woods, Frances (May 1, 2013). Chinese Lives: The People Who Fabricated a Civilisation . Thames & Hudson. pp. 120–121. ISBN9780500771471.

- ^ "China to Commemorate Ancient Patriot Yue Fei".

- ^ (in Chinese) Yue Ke, E Guo Jintuo Zhuibian ( 鄂國金佗稡編 )

- ^ Yue Ke, E Guo Jintuo Xubian ( 鄂國金佗續編 )

- ^ "Newly Recovered Anecdotes from Hong Mai'due south (1123–1202) Yijian zhi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i j 1000 l m n o p q r Wright, Arthur F., and Denis Crispin Twitchett. Confucian Personalities. Stanford studies in the civilizations of eastern asia. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1962 (ISBN 0-8047-0044-3)

- ^ a b c d east f 1000 h History of Song – Biography of Yue Fei (《宋史·岳飛傳》) (ISBN ?) (Come across also, 岳飛子雲 (Chinese only))

- ^ Deng (邓), Guangming (广铭) (2009). Biography of Yue Fei (岳飞传/岳飛傳) (in Chinese). ISBN978-vii-5613-4675-iv.

- ^ History of Song Affiliate 365 "飞生时,有大禽若鹄,飞鸣室上,因以为名."

- ^ a b Henning, Stanley E., M.A. Chinese Full general Yue Fei: Martial Arts Facts, Tales and Mysteries. Journal of Asian Martial Arts. Vol. fifteen #4, 2006: 30–35

- ^ a b c d due east f g Qian, Cai. General Yue Fei. Trans. Honorable Sir T.L. Yang. Joint Publishing (H.Chiliad.) Co., Ltd. (1995) ISBN 978-962-04-1279-0

- ^ a b c d east f Lian, Shou Yu and Dr. Yang, Jwing-Ming. Xingyiquan: Theory, Applications, Fighting Tactics and Spirit. Boston: YMAA Publication Center, 2002. (ISBN 978-0-940871-41-0)

- ^ a b c d Giles, Herbert Allen. A Chinese biographical dictionary = Gu jin xing shi zu pu. Kelly & Walsh, 1939 (ISBN ?) (Run into hither as well)

- ^ Song Ci. The Washing Away of Wrongs. Trans. Brian E. McKnight. Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan, 1981 (ISBN 0-89264-800-7)

- ^ Waters, T. Essays on the Chinese Language. Shanghai: Presbyterian Mission Press, 1889 (ISBN ?)

- ^ a b c d Liang, Shou-Yu, Wen-Ching Wu, and Denise Breiter-Wu. Qigong Empowerment: A Guide to Medical, Taoist, Buddhist, Wushu Energy Cultivation. The Way of the Dragon, Limited, 1996 (ISBN 1-889659-02-9)

- ^ "生有神力,未冠,挽弓三百斤,弩八石。學射与周侗,盡其術,能左右射。"

- ^ a b Jin, Yunting.The Xingyi Boxing Manual: Hebei Style'south Five Principles and Vii Words. Trans. John Groschwitz. North Atlantic Books; New edition, 2004 (ISBN 1-55643-473-1)

- ^ "岳飛及冠時,外祖父姚大翁聘請當時的槍手陳廣教授岳飛槍法。"

- ^ a b c d e Kaplan, Edward Harold. Yueh Fei and the founding of the Southern Sung. Thesis (PhD) – University of Iowa, 1970. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1970.

- ^ 及冠 jíguàn This leads to an English-Chinese dictionary. Type the characters "及冠" in for a definition.

- ^ A Report of the Gender and Religious Implications of Nü Guan (See page eighteen) (PDF)

- ^ Wu Tang Gold Bell Archived May 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (Chinese but)

- ^ Wu Tang pail builds up the Dan Tian Archived August 19, 2008, at the Wayback Automobile (Chinese only)

- ^ Chang, Shelley Hsueh-lun. History and Legend: Ideas and Images in the Ming Historical Novels. University of Michigan Press, 1990 (ISBN 0-472-10117-X), p. 104

- ^ Weisz, Tiberiu. The Kaifeng Rock Inscriptions: The Legacy of the Jewish Community in Ancient China. New York: iUniverse, 2006 (ISBN 0-595-37340-2), p. 18

- ^ Weisz, The Kaifeng Stone Inscriptions, p. 26

- ^ "Portrait Painting in Five Dynasties and Song Dynasty". Archived from the original on December eleven, 2006.

- ^ Zhang Jun, Han Shizhong, and Liu Guangshi were three of the four generals who stopped the state officials Miao Fu ( 苗傅 ) and Liu Zhengyan ( 劉正彥 ) from usurping the throne from Emperor Gaozong of Song. (Meet here as well)

- ^ Yue Fei's facelift sparks debate Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Prof. Hellmut Wilhelm's biography and accomplishments Archived February xviii, 2007, at the Wayback Car

- ^ Kaplan: pg. 5

- ^ Hammond, Kenneth James (2002). The Man Tradition in Premodern Communist china, Human tradition around the world, No. 4. Scholarly Resources Inc. ISBN0-8420-2959-i.

- ^ Toqto'a et al, History of Song, Chapter 365

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b Mote 1999, p. 300.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Lorge 2005, p. 56.

- ^ a b Mote 1999, p. 301.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 232.

- ^ Fan, Chengda. Rock Lake: The Poetry of Fan Chengda 1126–1193. Trans. J. D. Schmidt and Patrick Hannan. Ed. Denis Twitchett. Cambridge University Press, 1992 (ISBN 0-521-41782-1)

- ^ Wright, David Curtis. The History of Red china: (The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations). Greenwood Press, 2001 (ISBN 0-313-30940-X)

- ^ a b c d Leung, Shum and Jeanne Chin. The Secrets of Eagle Claw Kung Fu: Ying Jow Pai. Tuttle Publishing; 1st edition, 2001 (ISBN 0-8048-3215-three)

- ^ Lorge, Peter. State of war, Politics and Club in Early Modern China, 900–1795 (Warfare and History). Routledge; 1 edition, 2005 (ISBN 0-415-31691-10-)

- ^ "The Tomb and Temple of Yue Fei". hzwestlake.gov.cn. Archived from the original on March three, 2016. Retrieved Jan 18, 2020.

- ^ Markam, Ian S. and Tinu Ruparell. Encountering Faith: An Introduction to the Religions of the World. Blackwell Publishing Professional, 200 (ISBN 0-631-20674-four)

- ^ Olson, James S. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China. Greenwood Press, 1998 (ISBN 0-313-28853-iv)

- ^ Guy, Nancy. Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan. University of Illinois Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-252-02973-9)

- ^ a b "隗顺是谁?如果没有了他岳飞可能就尸骨无存了". 趣歷史. 趣歷史. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ Tang, Xianzu. The Peony Pavilion: Mudan ting, 2d Edition. Trans. Cyril Birch. Indiana University Press; 2nd edition, 2002 (ISBN 0-253-21527-7)

- ^ a b "Trapped Backside Walls: Ming Writing on the Wall – Prc Heritage Quarterly".

- ^ Li, Y. H. & Lu, D. Southward., eds (1982), Chinese Idiom Dictionary. Sichuan Publishing, Chengdou.

- ^ Yue Fei'due south Tomb Archived December eight, 2006, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ "Archaeologists to Earthworks of Possible Tomb of Qin Hui". china.org.cn. Xinhua News Agency. December 27, 2006. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ 俞, 荣根; 徐, 泉; 王, 群 (2012). 孔子,还受国人崇敬吗. 中国民主法制出版社. p. 87. ISBN9787516202241.

- ^ Frantzis, Bruce Kumar. The Power of Internal Martial Arts: Combat Secrets of Ba Gua, Tai Chi, and Hsing-I. North Atlantic Books, 1998 (ISBN 1-55643-253-4)

- ^ Eagle Claw Fan Tsi Moon & Lau Fatty Mang'due south History – Part I Kung Fu Magazine, Archived September 6, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Eagle Claw Info". Archived from the original on May 2, 2007.

- ^ Leung, Shum. Eagle claw kung-fu: Classical northern chinese fist. Brendan Lai'south Supply Co; 2nd ed edition, 1981 (ISBN B000718VX0)

- ^ a b c d Lin, Jianhua. Form and Will Boxing: One of the Big 3 Internal Chinese Body Boxing Styles. Oxford University Printing, 1994 (ISBN 0-87040-942-5)

- ^ Sun, Lutang. A Report of Taijiquan. North Atlantic Books, 2003 (ISBN ane-55643-462-6)

- ^ James, Andy. The Spiritual Legacy of Shaolin Temple: Buddhism, Daoism, and the Energetic Arts. Wisdom Publications, 2005 (ISBN 0-86171-352-4)

- ^ Pei, Xirong and Li, Yang'an. Henan Orthodox Xingyi Quan. Trans. Joseph Candrall. Pinole: Smile Tiger Press, 1994. See also, Xing Yi Quan (Mind-Form Battle) Books Scroll down, 5th book from the top.

- ^ Heart Chinese boxing emphasizing flexibility and confusing the opponent (Chinese only)

- ^ Lu, Shengli. Gainsay Techniques of Taiji, Xingyi, and Bagua: Principles and Practices of Internal Martial Arts. Trans. Zhang Yun. Blue Snake Books/Frog, Ltd., 2006 (ISBN 1-58394-145-two)

- ^ Wong, Kiew Kit. Fine art of Shaolin Kung Fu: The Secrets of Kung Fu for Self-Defense Health and Enlightenment. Tuttle Publishing, 2002 (ISBN 0-8048-3439-iii)

- ^ "Ji Xing – Chicken Form". emptyflower.com. Archived from the original on Feb 21, 2009.

- ^ "Ji Long Feng". emptyflower.com. Archived from the original on Feb 13, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Chuo Jiao Fist Archived February 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fanzi Quan (Tumbling Chuan) Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ Yuejia Quan (Yue-family unit Chuan) Archived February three, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ HISTORY & DEVELOPMENT OF CHUOJIAO Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming. Qigong Massage, 2d Edition: Fundamental Techniques for Health and Relaxation. YMAA Publication Eye; 2nd edition, 2005 (ISBN 1-59439-048-7)

- ^ Bisio, Tom. A Tooth from the Tiger's Mouth: How to Treat Your Injuries with Powerful Healing Secrets of the Corking Chinese Warrior. Fireside, 2004 (ISBN 0-7432-4551-two)

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming. Qigong Meditation: Embryonic Breathing. YMAA Publication Heart, 2003 (ISBN ane-886969-73-6)

- ^ Qian, Cai. General Yue Fei. Trans. Honorable Sir T. L. Yang. Joint Publishing (H.One thousand.) Co., Ltd. (1995) ISBN 978-962-04-1279-0

- ^ Chuojiao (thrusted-in feet) Archived December sixteen, 2007, at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ Shi, Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong. Outlaws of the Marsh. Trans. Sidney Shapiro. Beijing: Foreign Linguistic communication Printing, 1993 (ISBN vii-119-01662-8)

- ^ Yuen, Man Kai. Northern Mantis Black Tiger Intersectional Battle. Wanchai, Hong Kong: Yih Mei Book Co. Ltd., 1991 (ISBN 962-325-195-5), pg. 7

- ^ a b Yuen: pg. 8

- ^ James T. C. Liu. "Yueh Fei (1103–41) and Cathay'south Heritage of Loyalty". The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 31, No. ii (February. 1972), pp. 291–297

- ^ Hummel, Arthur West. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Authorities Printing Function.

- ^ Peter C Perdue (June xxx, 2009). China Marches Due west: The Qing Conquest of Cardinal Eurasia. Harvard University Press. pp. 253–. ISBN978-0-674-04202-5.

- ^ Peter C Perdue (June xxx, 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Primal Eurasia. Harvard University Press. pp. 331–332. ISBN978-0-674-04202-v.

- ^ Eugene John Gregory, August 31, 2015, DESERTION AND THE MILITARIZATION OF QING LEGAL CULTURE p. 204. (PDF)

- ^ Cheung (2015), p. 18.

- ^ "Nigh ten,000 descendants of Song general Yue Fei in Anhui". WordPress.com. June 13, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ "岳飞冤案的证人隗顺 【明慧网】". www.minghui.org.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 686.

- ^ Tao 2009, pp. 686–689.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 687.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 299.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 305.

- ^ BARANOVITCH, NIMROD. "Others No More: The Irresolute Representation of Non-Han Peoples in Chinese History Textbooks, 1951–2003." The Journal of Asian Studies 69, no. ane (2010): 85–122.

- ^ 水战杨么----岳飞(南宋) July xx, 2009国防部官网

- ^ 隆重纪念民族英雄岳飞诞辰910周年 2013年03月21日人民日报海外版

- ^ 关于古代"民族英雄"的再认识

Sources [edit]

- Franke, Herbert (1994). "The Chin dynasty". In Denis Twitchett, Denis C.; John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–320. ISBN978-0-521-24331-5.

- Lorge, Peter (2005). War, Politics and Guild in Early on Modern Red china, 900–1795. Routledge. ISBN978-0-203-96929-8.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN0-674-44515-five.

- Tao, Jing-Shen (2009). "The Move to the South and the Reign of Kao-tsung". In Paul Jakov Smith; Denis C. Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of Red china: Volume 5, The Sung dynasty and Its Precursors, 907–1279. Cambridge University Press. pp. 556–643. ISBN978-0-521-81248-1.

- Cheung, Raymond (2015). Tony Holmes (ed.). Aces of the Democracy of Red china Air Strength. Oxford, Englang; New York City, NY: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-ane-4728-0561-4.

External links [edit]

- Works by Yue Fei at Project Gutenberg

- Works past or about Yue Fei at Internet Annal

- Works by Yue Fei at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "History of the Song" Chinese Wikipedia entry (in Chinese)

- 470 book version of the "History of the Song" (in Chinese)

- The Story of Yue Fei (in Chinese)

- "Yue Fei's Biography" from the History of the Song (in Chinese)

- "精忠报国 Utmost Loyalty to the Country", a famous Chinese song related to Yue Fei (in Chinese)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yue_Fei

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Will You Cry for the Villagers Again Chinese History"

Posting Komentar